Ways to explore the attributes and symbols of subcultures

Derek Ridgers is a British photographer known for his photography of music, film and club/street culture.

I should state up front that when I started what turned out to become my photographic investigation of British youth subcultures, it was completely unplanned and very informal. To begin with, it was no sort of a study or project. I’m not an anthropologist or a sociologist. At that point, I wasn’t even really a photographer. I was simply an office worker with a 35mm camera. Not, at that point, even a particularly keen amateur. To be completely honest, when I started photographing British youth subcultures in 1976, it was just an opportunity to take some photographs. An easy option. It could just as easily have been any social subgroup that tolerated me photographing them — city bankers, construction workers, the homeless, Morris dancers or virtually anyone.

For me it just happened to be punks. And the reason it just happened to be punks was that I was a big music fan. I was going to gigs around London every week, photographing some of the bands I saw and in 1976 punk happened. Punk rock bands and their punk fans had started to appear at many of the gigs I was going to. So really, it was just photographic opportunism. I didn’t have the gumption to photograph the punks to begin with. I was far too shy and I didn’t know how they would react. I suppose, like most people, I assumed they would be aggressive and that it might be hard to get them to agree to being photographed. This turned out to be not the case at all, far from it. I sort of forced myself to work up the courage to do it and the punks I approached reacted well. I took some photographs of them and it set me off on what has become a photographic journey spanning six decades.

Nevertheless, I’m sure that the initial apprehension I felt was why not so many other photographers chose to shoot them in the early days. By 78/79, the shock element of punk had worn off, many other photographers joined me on that particular bandwagon and it was even possible to see small groups of punks in Piccadilly Circus and in the Kings Road cadging money off tourists who wanted to photograph them. I was lucky I suppose, to have got in there early. Quite a few of my photographs of the early punk rockers got exhibited and published and, after that, I started to take my photography a little bit more seriously. I decided to consolidate my new ‘career’ and look for another youth subculture to focus my camera on. At first I didn’t choose the skinheads. At that point, I didn’t even know they existed. Of course, I’d known of the skinheads of the 1960s. As a teenager, who wore glasses, I’d done my level best to avoid them. In the 1960s they were initially called ‘Peanuts’ not skinheads in the part of West London I grew up in. But I hadn’t actually seen any bone fide peanuts/skinheads since about 1969. I thought it was an aspect of youth subculture that had totally died out.

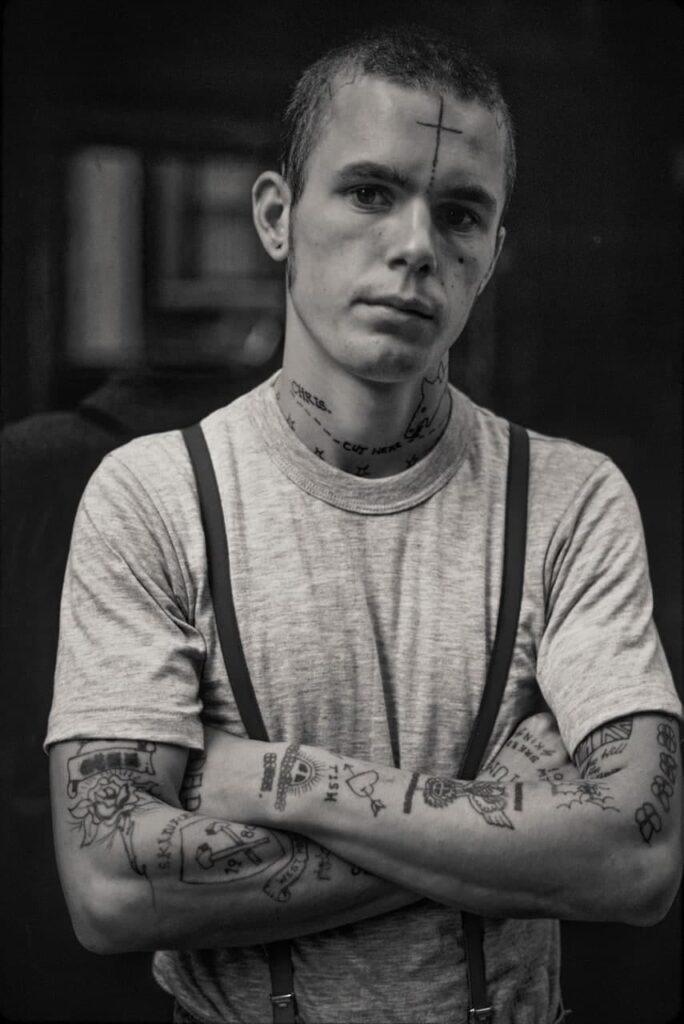

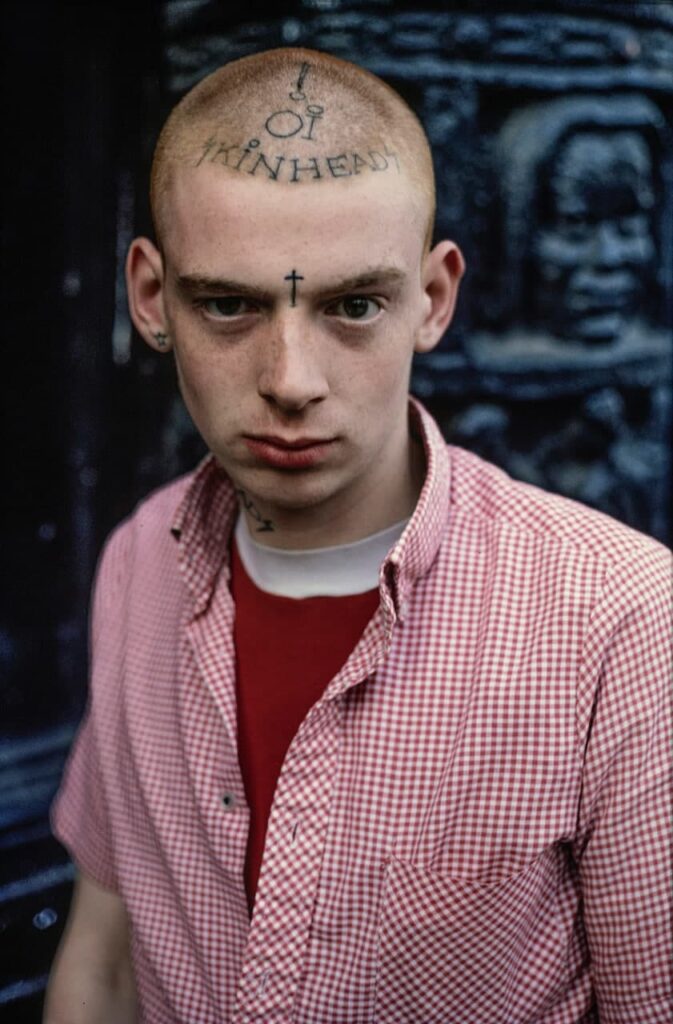

One night, I was in a small Soho nightclub taking photographs of a bunch of colourfully dressed up kids that were part of a group that would soon go on to become known as New Romantics. Another small group of young men saw what I was doing and came over and asked me if I wanted to photograph them too. I did. They were dressed up almost exactly like the skinheads I’d seen in the late ‘60s. Braces, big boots, Sta-Prest trousers or Levis, Ben Sherman or Fred Perry shirts and, obviously, very short hair. They seemed friendly enough. A little boisterous but not at all aggressive. (First photograph below).

I did think at this point that they might be a group of fashion or art students dressing up as skinheads. I couldn’t have been more wrong. In chatting to them they asked me if I wanted to accompany them on their next bi- annual Bank Holiday jaunt to the seaside. They told me there would be hundreds of their skinhead friends there and I’d be able to get some great photos. Great photos was certainly what I was looking to do so I readily agreed. It wasn’t until I met them and their friends that day at Fenchurch Street station, in London’s East End, and began to really converse with them, that I realized they were not arty, fashion students at all. These were the real thing. On the journey to Southend, many of them were eager to proselytise and let me in on their political and social views.

I was shocked. Actually ‘horrified’ would be a more accurate word. I very clearly remember thinking «OMG people need to hear this some of this stuff”. This was really when my project was born. At that moment. I hadn’t intended to interview any of them but by now I knew I had to. I suppose, they might have assumed, because of my obvious interest in them, that I was a reporter or a member of the media. I certainly didn’t mislead them on this point. They really didn’t seem particularly curious about who I actually was.

The skinheads I met and chatted to on that day, and in the six months or so afterwards when I made my taped interviews, all had very bleak and negative social views. They made it crystal clear to me, right from the off, that they didn’t like gays, immigrants, foreigners, people of colour, jews, politicians, the police, the media, the middle classes and or even sometimes their own parents. They most definitely didn’t like punks, mods or any other British youth subculture. The only people they really seem to like were other skinheads. Within about ten minutes, in one of my first conversations on the train to Southend, I heard about “dirty, lazy immigrants coming over here, taking our jobs”. I should state right here, for the record, that in the years since I took my photographs (which ultimately stretched out over the years 1979 — 1984) and made my interviews, I’ve learnt that not all skinheads had these kinds of extreme views. I know this now. From many one-to-one discussions and also from listening to people like Don Letts and Gavin Watson. I’m very happy to acknowledge that this was the case.

However, it’s also important for me to say that that wasn’t how it seemed to me at the time. Furthermore, once one was able to scratch the surface a little, one found BAME skinheads, skinheads who were white but very obviously not British, gay (but not necessarily out) skinheads, middle class skinheads and even a one or two Jewish skinheads. They seemed to be accepted by the other skinheads. What seemed like the crucial thing was that they were skinheads and they shared (most of) the same ideology. I spoke to a few BAME skinheads and asked them about racism. Their attitude always seemed to be that they themselves were okay but it was the others. There was always someone of different ethnicity or pigmentation that they didn’t like. Someone further down the social pecking order, as they saw it. The first time I met a skinhead who was avowedly non racist and politically left wing was in 1983. Whilst working for the music magazine NME, I met Chris Dean of the band The Redskins. I have no real doubt that I had probably met others with a similar perspective before but they, for whatever reason, chose to keep their views to themselves.

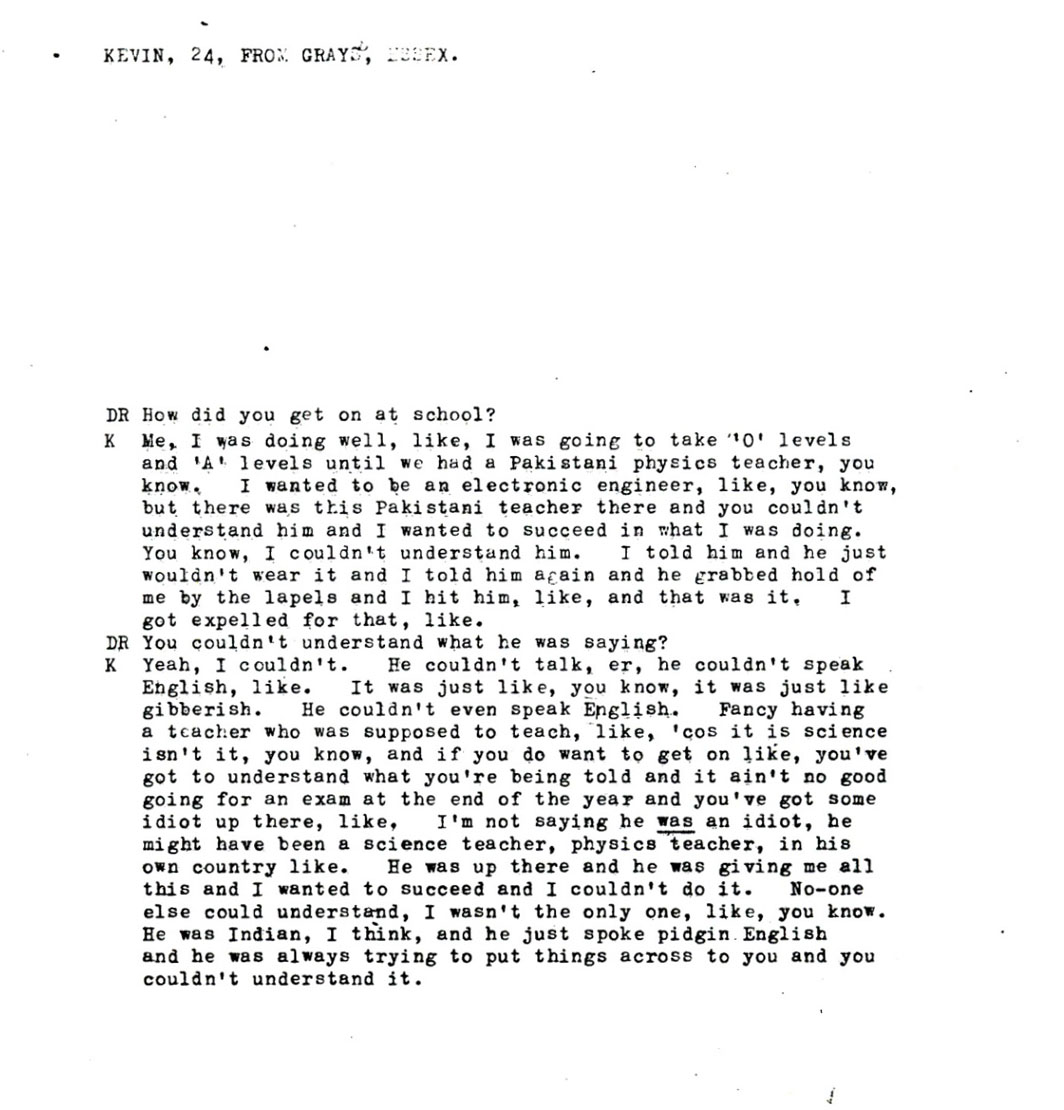

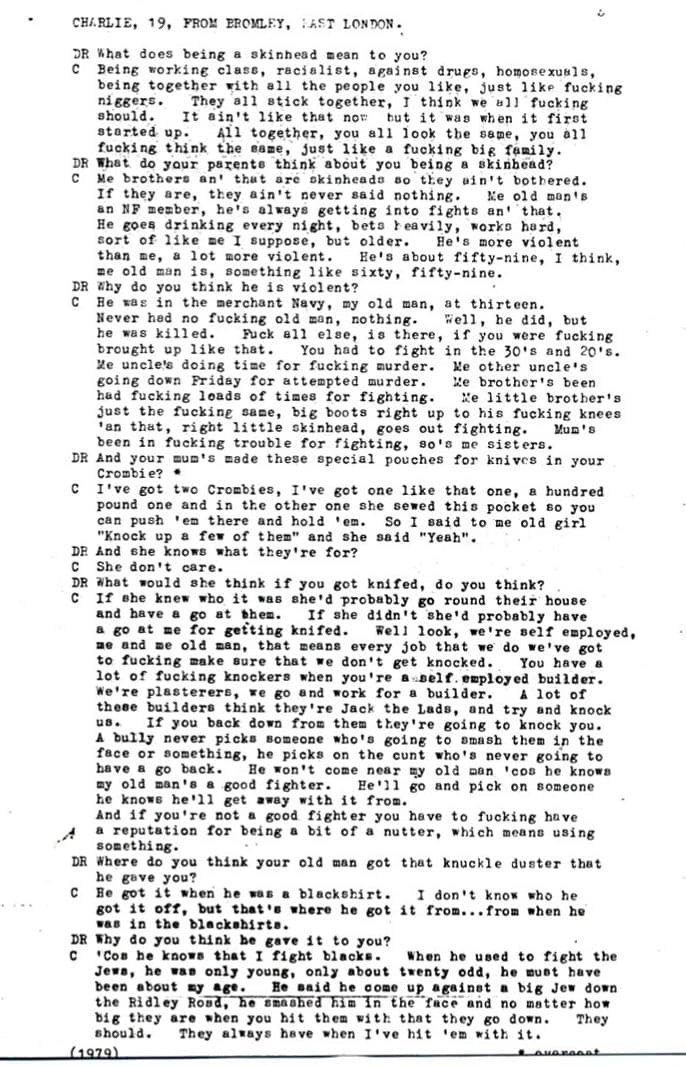

No one has to take my word for any of this because almost all the skinheads during the period I was shooting them would announce their view point non verbally via their clothing (mainly t-shirts) badges and tattoos. These can be seen in my photographs. And the Sieg Heil salute was ubiquitous. I edited out a lot of the Sieg Heiling from the photographs I allowed to be published over the years but it’s all over the contact sheets. I would guesstimate that a large majority of skinheads I photographed displayed some sort of non verbal expression of their opinions. Many times this would be to do with their musical affiliations as well, not only their social and political views. Eventually I made about a dozen taped interviews, excerpts of which were transcribed and printed be displayed alongside the photographs at my show ’Skinhead’. Chenil Gallery, Chelsea 1980. (I’ve included a few of these at the end). The visitor books for that show (which I retained), exist as further evidence of how things were presented at the time. There was no security at the ’Skinhead’ show and attendees were free to write or draw whatever they liked in the visitor book. One and bit visitor books were filled up. The messages are mostly very one sided but there are also some very sad and poignant ones.

In the years since, I’ve had my share of criticism of this work. Although, I have to say, seldom from the skinheads themselves. People’s criticism falls two ways. They either think that I’m an apologist / advocate for the skinheads and, at the very least, subliminally promoting their racist and violent ideology. Or they think that I was very much against the skinheads and I was just trying to show them up in the worst possible light. Neither of these views are correct. I was simply trying to be objective and tell the truth. I wanted my photographs and associated material to speak for itself without undue interference from me. It’s only in the years since that I’ve learnt true objectivity is impossible. I just didn’t realise this then? I have already said, I was a rank amateur when I was doing it.

A few words about my approach, which seemed to work well and keep me safe (although I’m duty bound to say that there was more than a little luck involved in the latter). My approach was quite low key but always very direct. I’d always walk straight up to someone and speak to them in exactly the same way I’d speak to anyone else. I was always polite and I’m softly spoken and I wanted the skinheads to see that I was genuine and sincere. Whenever I was asked by any of the skinheads why I wanted to photograph them, I told them that I wanted to do a show. I never added much to that. I always told them the bare minimum I thought I could get away with because I didn’t want them second-guess me or give me what they thought I might have wanted.

A few of them would ask me if I was working with the police or for the newspapers. I disabused them of that and they always seemed to accept my word. Whenever any skinhead asked me about my own political or social views, I answered them honestly but as briefly as I thought would be acceptable. My politics at that time were firmly of the Left. I was a paid up, active member of the Labour Party throughout the time I was photographing the skinheads. Very few of the skinheads I met were stupid. I think they could broadly tell what my views were without me needing to spell it out. I’m not by any means an alpha male but I’m not easily intimidated. In any group conversation I spend 95% of the time listening. I don’t have any tattoos, I wear glasses and during the winter months I wear a duffel coat. In the summer, an open neck shirt, cardigan and jeans. I was like that then and I suppose I still dress the same way now.

I don’t swear much. Some skinheads said that I was not like them because I didn’t swear “enough».

I was always friendly to the skinheads I met but I didn’t actually want to become anybody’s friend. I wanted to keep my wits about me and keep a professional distance. I’m not the clubbable type and I know that I don’t smile enough.

I mention my own character and appearance here only because my approach seemed to work.

The photographer Nick Knight, when he was photographing the skinheads at around the same time as me, dressed as a skinhead. Gavin Watson was a skinhead when he was making his work too. Those approaches must have worked for them. So, horses for courses, I guess. As a photographer, one’s own personality is an important part of the equation too.

Personally I think it’s important to not allow your presence to affect the situation too much but you do have to be straightforward and very clear about what you want. There will be times when you can stand on the margins and try to become invisible and other times when you have to get right up close in someone’s face. You have to always judge the right moment.

When I wanted to take photographs, I’d almost always ask first if it was okay. They never seemed to mind. If I wanted to take more candid type photographs, I’d still be fairly obvious about it. My approach was never sneaky or furtive. I was never crouched behind the furniture.

The rest of the time, I kept my camera in my bag. The few times when I was in a pub or club and I sensed danger, I would just leave immediately. I never hung around long enough to learn if my sense was correct or not. I always tried to keep a keen sense of what was going on around me and what was happening behind me or outside of the immediate group I was photographing. If I saw anyone who I thought might be looking at me or talking about me from across the room, I would usually see that as a signal to leave. If things started to get too rowdy or too drunken, this would also be my going home time. That said, whilst I was with the skinheads, I saw virtually no fighting and certainly no serious violence. A lot of larking about and rowdy behaviour but then all teenagers can be that way. The only fighting I saw was on the Bank Holidays at the seaside and it was usually over very quickly. I came close to being beaten up by skinheads on only a handful of occasions and in all but one time, I was helped out and rescued by other skinheads. I liked some of the skinheads despite their appalling views. Some were very hard not to like. I thought most of them were basically decent kids who been misled and badly misinformed. Kids who’d grown up in very difficult circumstances and either been failed by the social services or expelled or in other ways marginalised by the school system. I couldn’t have spent so much time with them if I hadn’t liked some of them so much. I can’t really explain this aspect. Maybe I felt sorry for them.

I would not recommend my approach to others. When I started, I was very naive and had no idea what I was letting myself in for. If I knew then, what I know now, I wouldn’t have started.

I hope the material has some validity but that’s now for others to decide.

A small, edited selection of the original interviews:

The interview at my show “Skinhead”. Chenil Gallery, Chelsea 1980.