The New Berlin: Offbeat, disruptive, and imperiled

Paul Hockenos is a World Policy Institute fellow and author of “Berlin Calling: A Story of Anarchy, Music, the Wall, and the Birth of the New Berlin” (The New Press, 2017).

By Paul Hockenos

Berlin’s creative industries[1] and the city’s hip, countercultural branding enabled the metropolis on the banks of the Spree to pick itself up and prosper after a long, agonizing post-Wall transition period. But, to its detriment, the city has neglected to aid its creative class—artists and artisans, designers, musicians, filmmakers, writers, performers, small club owners—in the ways that matter most, namely by preserving the conditions conducive for artists and other original not-exclusively-for-profit enterprises to thrive. While tapping its cool, the city undermines its source with a growth strategy that offers up to investors and developers the very ground beneath the creative set’s feet. Gentrification, population growth, commercialism, and mass tourism threaten to undercut the processes that invigorated and shaped the city, making it attractive to professionals and tourists in the first place. If these trends continue unabated, Berlin will find itself in the same condition as Europe’s overpriced, glass-and-metal clone cities, the innovators pushed out of the very neighborhoods, and perhaps even the city, they imbued with zest in the first place.

***

The disappointment of the developers and city planners, investors and politicos with post-Wall Berlin’s economic washout in the 1990s and much of the aughts was profound and bitter. In the aftermath of the Berlin Wall’s breach in November 1989, and with Berlin’s metamorphosis into one city again—as capital of a united Germany— a league of development professionals envisioned a sweeping transformation of the city that would quickly pay off big. Without consulting the people of Berlin, a total of 3.43 million freshly unified easterners and westerners, the city set in motion plans to make Berlin a world capital of finance and commerce. Berlin would have skyscrapers in a completely rebuilt city center. Big urban blocks of office buildings, congress halls, and high-end apartments would stand where the Wall had been. The modernist eyesore of Alexanderplatz in former East Berlin would become “Berlin’s Manhattan.” There’d be a new mega-size airport like Frankfurt’s, and all of it would be ready by 2000 when Berlin could, if chosen, host the summer Olympics.

As it happened, very few of these high-flying plans ever materialized. Certainly, there was head-over-heels construction in the years following the Wall: the malls, cinemas, and high-rises of Potsdamer Platz, for example, rose from the 150-acre no-man’s land that the Wall had bisected. Nearby, Berlin built a towering central train station, Europe’s largest, and ultra-modern light-flooded buildings to house the federal government as well as the MPs of the Bundestag, which itself was completely retrofitted for the purpose and adorned with a striking glass cupola. Yet the leagues of anticipated investors with deep pockets stayed away. And with the exception of winning recognition as the world’s biggest and noisiest construction site, the city couldn’t settle on an image and development strategy for the new Berlin.

In fact, after designing and then ditching one plan after another for the city, it was about a decade after unification that the city finally awoke to the nature of its unique cachet, something missing from Frankfurt, Hamburg, and Munich: a gritty, inventive, do-it-yourself underside that the city itself had done nothing to nurture and, paradoxically, had even tried to conceal. Around the year 2000, planners realized that Berlin was attracting droves of young, innovative, educated people who sought out the city explicitly because of its rough edges, low rents, and unconventional flair. Tourists came in ever greater numbers for the clubs and night life. Commercial interests followed: Some bolstered the creatives, such as record labels and publishing houses, but many others, too, that just wanted a place in this hip, new Berlin, such as media ventures, IT companies, and real estate developers, among many others.

The city leapt onto the wagon with the zeal of the converted, boasting about the Berlin’s untended crannies, which could be used for all manner of self-styled projects and small businesses. “The ‘creative city’ mantra was integrated into Berlin city marketing,” writes sociologist Claire Colomb, “with various campaigns selling the constant change, experimentation, and trend-setting taking place in the city as significant attractiveness factors. Some of the ‘off-beat,’ alternative, or underground cultural and artistic scenes were officially integrated into place, marketing strategies, for example the techno and clubbing scene.”[2]

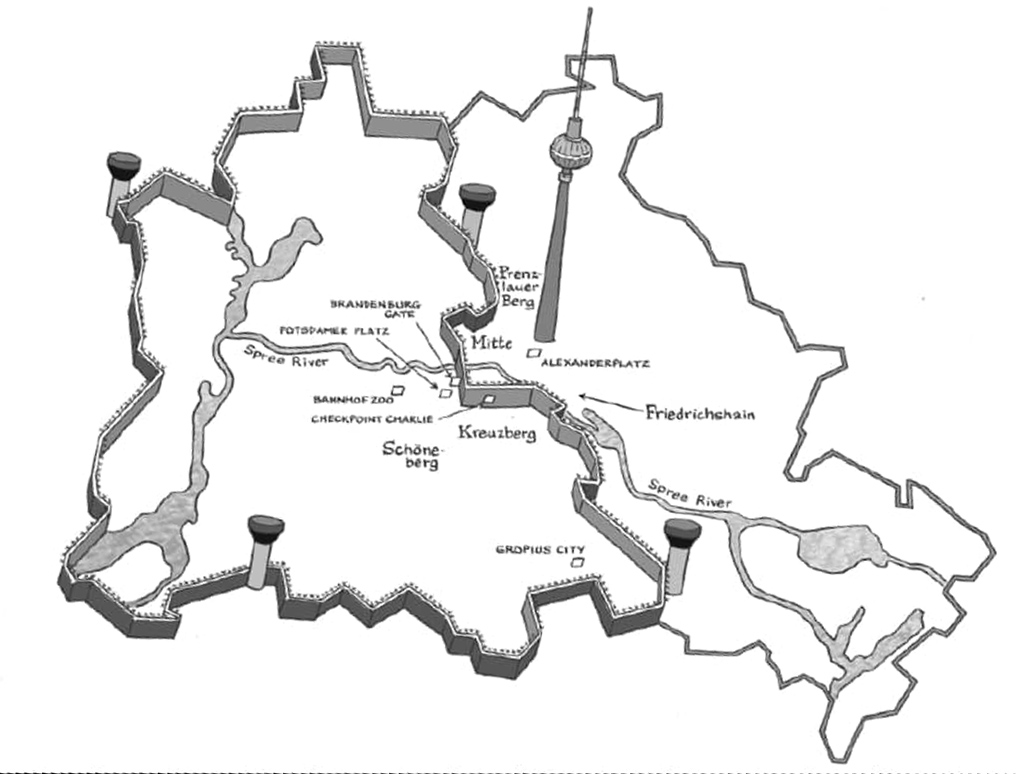

The planners couldn’t have guessed that the torrent of cultural enterprises and visitors streaming into Berlin had only just begun. By 2002, the creative economy had breathed life into 18,000 businesses that supported 90,000 jobs, 8 percent of the city’s workforce. By 2012, there were nearly twice as many such enterprises and jobs, and an astounding gross of $21.5 billion, 10 percent of Berlin’s total. Two years later, the branch had grown by 20,000 more jobs. Something about Berlin was prompting startups in diverse sectors, which by the 2010s vaulted Berlin to startup champion of all of Europe. Meanwhile, Berlin had overtaken Rome as tourists’ third most desired destination in Europe, behind only Paris and London. These visitors weren’t coming for the hoch cuisine (indeed, there is none in Berlin) but to browse through the sprawling flea market on a Sunday morning in Mauerpark, explore the art galleries on Brunnenstrasse, or just wander the streets of Kreuzberg and Prenzlauer Berg. Gay tourism in Berlin constituted a world and industry unto itself, as it long has.

Berlin as the fertile site of this inspired upsurge and magnetic draw has explanations that reach back into its distinct past. The city during its division and then in the decade following the Wall offered iconoclasts and demimonde two crucial elements that enabled them to thrive in its environs: Freiraum (free space) and Freizeit (free time). The new generation that has flocked to the city since then might not know it, but it was this wealth that had made both East and West Berlin redoubts for free spirits and the artistically inclined, enabling them to grow extraordinarily inventive subcultures in the late 1970s and 1980s, well before German unification.

A bizarre irony, the phenomenon integral to the unique biotopes of East and West Berlin was the Berlin Wall, the most prominent symbol of a divided Europe and Soviet communism’s brutal logic. Although it was the Soviet-backed Communist regime of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) that threw up the cinder block and barbed-wire partition in 1961, West Berlin found itself the city surrounded by the Wall. The 106-mile trip from the mainland of the Federal Republic, known as West Germany, went through East Germany along special “transit highways” from which one was forbidden to stray. In order to enter West Berlin, one had to pass the East German border guards, which could take minutes or hours, one never knew, and usually longer if your passport read “United States of America.”

Such a high negative, among many others, made West Berlin an unlikely place for the cautious or career minded. In fact, West Berlin’s disadvantages challenged the city’s administrators to just keep the city populated, which it addressed largely by subsidizing almost everything in the city, including its bohemia, most of whom/which harbored staunchly left-wing political views. By the 1980s, even I knew about West Berlin’s reputation, and arrived in autumn 1985, a twenty-two-year-old college grad looking to escape upstate New York, Reagan-era America, and the pressure to choose a career. After all, David Bowie and Iggy Pop had produced some of their finest work there in the 1970s. I had seen the fighting between house squatters and police on the evening news. I knew about the Free University’s reputation as a hub of critical social thought. And, perhaps best of all, I didn’t know a soul there.

But what I didn’t realize was just how many others there were in West Berlin fleeing something: be it conscription in the West Germany army, provincial hometowns, or East bloc spy services. And by the end of the 1970s and through much of the 1980s, a vibrant subcultural scene flourished in this environment, word of which leaked out through the militarized borders attracting even more talent, such as Nick Cave, Depeche Mode’s Martin Gore, photographer Nan Goldin, Lou Reed, and many others. The world-famous fashion designer Claudia Skoder began in West Berlin, as did some of Germany’s most renowned modern artists, among them Jörg Immendorff and Martin Kippenberger. Moreover, the 1960s student movement and the New Social Movements of the seventies that followed in its wake – the environmental, anti-nuclear energy, women’s, and peace campaigns – had also stamped their imprint on the city’s western zones. And the “alternative movement,” a mishmash of dropouts and idealists committed to off-the-grid projects and lifestyles, had established a parallel economy ranging from organic food co-ops to basement movie theaters. Their projects combined innovations in everyday life, politics, and culture that were tightly interwoven.

In the 1980s, West Berlin’s most gifted artistic innovators moved in the circles of the Brilliant Dilettantes,[3] an informal group of artists and musicians who took punk rock’s do-it-yourself ethos to heart. (Evidence that Berlin’s experiments in daily life, politics and culture go back even further that the 1960s, the Dilettantes name and much of their inspiration hailed from the post-World War I Dada movement.) Perhaps the most celebrated of the many projects and endeavors – or at least the most spectacular – was the industrial band Einstürzende Neubauten (literally: collapsing new buildings), which served as an inspiration for industrial bands forever after from Nine Inch Nails and Marilyn Manson to Rammstein. The Neubauten made music with sledgehammers and concrete slabs, buzz saws and a mélange of industrial refuse. The seeds of electronic dance music were sowed in West Berlin, too, not least by musician and club owner Hegemann’s Atonal Music Festivals, a pioneering project in electronic music. The Dilettantes and others in their adopted home had freizeit and freiraum that creatives today can’t imagine.

Many West Berliners didn’t know it – in fact, many could/couldn’t have cared less about East Berlin – but across the Wall existed another truncated city in which richly imaginative projects had taken root in the old turn-of-the-century apartment buildings and abandoned factories there, too. Like West Berlin’s creations, they interwove everyday life, politics, and subculture. But in a state ruled by a no-nonsense dictatorship, their activities and products constituted sedition and were punishable by law. Indeed, the stakes for its protagonists were inordinately higher than for their peers in West Berlin, and their extreme means of innovation and improvisation reflected this. In the GDR, innovation outside the parameters of that prescribed by the state was understood as a threat.

The possibilities of expression for independent-minded citizens who not only bristled under the dictatorship but sought to speak out against it was extremely limited. Par for the course in the Soviet bloc, all parties other than the communist party and its satellites were banned, and freedom of assembly and other forms of organization were tightly controlled by the state. There had been nothing like West Germany’s student movement or the New Social Movements in East Germany. (In fact, there were attempts to organize around similar themes in the GDR, but they were either crushed or more subtly undermined.) There was no easily accessed freiraum in a paternal state that believed it have the last say on everything. The one institution that had managed to carve out some freiraum was the Protestant church, and indeed under the wing of its more intrepid pastors a counterculture and a free art scene managed to wage opposition to the regime – and have a hand in eventually overthrowing it.

Culture was particularly tricky terrain as it was much harder for the state to control than overt political activities, and its message always open to interpretation. Thus it was through counterculture that the GDR’s political opposition in the 1980s sought to pry open intellectual space and make politics. East Berlin had its own bohème that boasted experimental bands, visual artists, sculptors, and even an underground film scene. Punk rock was particularly important, especially for the GDR’s youngest, urban-based generation of radical critics. (This was never more than a tiny splinter of the youngest generation at large, but its spirit and intent scared the communists enough to prosecute them, sending their protagonists to jail, into the army, or into exile across the border.)

“The state said that you’re nothing and can do nothing without it,” explains Heinz Havemeister, a musician born in East Berlin and co-author of a book on the GDR’s independent music. “The do-it-yourself thing circumvented the hierarchy of the GDR’s music sector, the whole system of the youth clubs and censors and everything.”

When the Wall toppled, the subcultures from East and West Berlin collided into one another in the ruins of East Berlin, producing something completely new in a burst of eccentric experimentation. The East German officials, their authority undermined or annulled, stood aside while over two hundreds buildings were squatted: by East Germans, West Germans, and protagonists from across Europe. For the first time since the early 1930s, Berlin was open to the world again. There was freiraum for just about anybody with a crowbar and a good idea. The eleven months between the Wall’s toppling and unification was aptly dubbed the “miracle year of anarchy,” which for many of Berlin’s impresarios, like those behind the giant electronic dance music clubs – such as Tresor, Planet, WMF and E-Werk – extended into the late 1990s. The off-grid countercultures exuded powerful, intensely political currents that inspired newcomers who came in their wakes, even those too young to remember a divided city.

Keeping Berlin Unique

Berlin today is the respected capital not only of the unified Germany but, arguably, of Europe itself. Germany’s muscular economy stands second to none on the continent, and it is to Berlin, not Brussels or Paris, that U.S. presidents and other world leaders look when crises strike between the Atlantic and the Urals. Far beyond Potsdamer Platz, Berlin’s manic growth has smoothed over many of its edges, spackling its once ubiquitous feral lots, and erasing all signs of the East Germany’s infamous wall, too. The developers and real estate brokers who survived the punishing 1990s are finally seeing their dreams of wealth fulfilled.

The quandary facing Berlin is whether a world-class metropolis so buff with gravitas can remain idiosyncratic, sharply critical, and experimental—inviting to nonconformists as well as IT professionals and statesmen. So far, Berlin has pulled it off, though just barely, and not without casualties. Many of Berlin’s defining projects of the post-Wall era—such as the squatted ruin called Kunsthaus (Art House) Tacheles, the dance clubs Planet and Bar 25, the indie locales IM Eimer and Knaack, to name just a handful—have fallen to gentrification and are now gone forever. The electronic dance music clubs are overrun with party tourists. The list of subcultural landmarks, Mauerpark included, currently fighting for their lives is long and heart-wrenching. Rents have skyrocketed in the former bastions of the subculture—the districts of Prenzlauer Berg, Kreuzberg, and Friedrichshain—so much so that many artists can’t possibly afford to live there. The district of Mitte, one of the post-Wall years’ hubs, is now the playground of Berlin’s well-off professional class; flashy cocktail bars and boutiques having long since replaced the hole-in-the-wall cafés.

Among the developing world’s cities, this trajectory is not exclusive to Berlin, as anyone who experienced New York, London or San Francisco in the 1970s knows. As it climbed out of its 1990s trough, rents in Berlin inched upward. Although higher rents were probably inevitable, the city possessed the means to curtail excesses and augment social housing. Instead, it sold off most of the social housing on the east side, the revenue from which it loaned back to the new owners to renovate the housing stock. Block upon block of the historic buildings benefited tremendously from the full-scale renovations that they’d been denied since the war. The reconstructed facades and fresh paint did the neighborhoods wonders, but privatization meant leaving the housing of the poorly paid, and the inventive minds among them, to the fate of the market.

The gentrification cycle

I experienced Berlin’s gentrification from the front lines as it rippled outward from the city center. Downtown Mitte was hit first, which is where I lived in the early 1990s on Friedrichstrasse, the grand shopping mile of the 1920s. I sublet a ground-floor apartment with the luxurious features of central heating and telephone (amenities one did not take for granted on the east side). The spot was set back from busy Friedrichstrasse in an enclave that had been built by the Huguenots, French Protestants who’d fled 17th-century France. Outside my balcony was a wild thicket through which I could hear elephants, horses, and other animals at the Charité’s veterinary clinic next door. The Huguenot Quarter was so desirable in the GDR decades that the party reserved it for prominent East Germans, among them the Dadaist artist John Heartfield and philosopher Ernst Bloch (both long deceased by the time I arrived).

My cushy setup there was typical of the times. My “landlord” was a GDR-born engineer whose name was on the lease. Having left for a job in Bavaria, he let his subsidized apartment to me, padding the rent (against the law) by a hundred dollars or so. But at $235 a month, I couldn’t complain. I left two years later as the storm of construction crept up Friedrichstrasse in my direction.

My next abode was in one of the old five-story tenements on Immanuelkirchstrasse in Prenzlauer Berg, about a 10-minute cycle from Friedrichstrasse. The cobbled street, lined with pear trees, sloped gently upward from the base of Friedrichshain Park to the Immanuel Church on Prenzlauer Allee. When I moved into a three-person apartment collective in 1994, the street only had a couple of businesses on it, one of which was the peaceful café Briefe an Felice (Letters to Felice) at the address to which the Czech-German writer Franz Kafka sent his famous letters to his fiancée, Felice Bauer. Across the street from my flat, a small coal yard operated out of a gap in the cityscape left by an Allied bomber. At my desk, I’d watch this scene straight out of the 1930s as the coal schleppers, black as ravens, stacked their back boards with briquettes and lugged them to the delivery truck. The gap let sunlight shine in all day long and afforded me an unobstructed view of the bulbous TV tower on Alexanderplatz. The neighborhood was still largely populated by its 1980s residents: low-paid workers, destitute types without formal employment, seniors, students, and the local bohemia. Since the Wall fell, outsiders like me had moved in too.

Throughout the 1990s, the street evolved slowly, if imperceptibly at first. Small businesses came and went quickly, such as shoe-repair shops, cafés, bars, erotic massage parlors, tiny artist studios-cum-galleries, liquor stores. Some of the poorer families migrated to the cement-paneled high-rise estates on Berlin’s periphery, while better-off families headed for Berlin’s green suburbs. As young singles gravitated to the neighborhood to replace them, local kindergartens and schools shut their doors. Quality nightclubs such as Knaack and Magnet dotted the map, as did the late-night Kommandantur at the base of the old water tower, a dive that the neighborhood piled into around midnight.

Barely two years later, gentrification was in full swing. Briefe an Felice and the coal yard had closed, the latter eventually replaced by a modern apartment building that blocked my cherished sunlight. The construction hullabaloo had crossed from Mitte into Prenzlauer Berg, commencing a 10-year process of refurbishment that prompted a relentless, top-to-bottom demographic turnover, which would change the Kieze, or neighborhoods, beyond recognition. I turned one of the bright, high-ceilinged front rooms of my spacious walkup into an office. But I couldn’t enjoy it. The jackhammers started at 6:30 a.m. and didn’t taper off until dark. At no point during the aughts was there not a renovation site in earshot.

In the meantime, my building was sold to eight parties living in the house. Although they weren’t collectivist-minded types, they wanted to run the house for the benefit of everyone in it. Their monthly meetings lasted for hours, but not as long as those of our next-door neighbors, who had turned their building into a cooperative, the structure itself owned by a nonprofit building association, every member of the co-op with one vote. This ownership model, with case-by-case variations, was the form that most of Berlin’s legalized squats eventually took.

The demographic shift in Prenzlauer Berg was unmistakable as young professionals and small upper-middle-class families moved into the handsomely refurbished buildings, by then some of the most coveted real estate in all of Berlin (and, by then, all with telephones and central heating). The newcomers’ cars clogged up both sides of the narrow streets. And the singles of the ’90s hooked up with one another to become the families of the aughts. Kindergartens reopened and playgrounds sprouted like dandelions as Prenzlauer Berg acquired the reputation as the family-minded fertility capital of Germany. Nowhere in the country—where for years deaths outnumbered births—were Germans having more children.

Almost all of my acquaintances were employed in the creative sector—as journalists, translators, musicians, designers—and most of them chose to sacrifice the security of nine-to-five for the freedom of flexible contract work. In addition to Berlin’s general affordability, this is possible thanks to a venerable institution called the Künstlersozialkasse, the Artists Social Insurance Fund, which offers a broad category of artists, including writers and translators, health and disability insurance, as well as matching social security payments, for a monthly rate gauged to income. The streets of Prenzlauer Berg came to be lined with bookstores, yoga studios, the co-working spaces of design firms and IT startups, translation collectives, and new media outfits. I currently share an office with a computer programmer, a professor of cultural anthropology, and a freelance film critic.

I, too, was a Prenzlauer Berg single who found a life partner and settled down. Our child attends one of the area’s kindergartens between the Kulturbrauerie—a former brewery that now houses cinemas, clubs, and a theater troupe—and super-trendy Kollwitzplatz. Typical Prenzlauer Berg, all of the kindergarten’s kids and their parents are white, educated, and gainfully employed, a striking contrast to the old West Berlin neighbourhood of Kreuzberg, for example, where ethnic diversity (mostly in the form of Turkish-background inhabitants) has survived even though the rents there have shot through the roof there too. The parents of my son’s pals come from eastern and western Germany, and across the European Union. But not from Turkey or Eastern Europe. And, of course, there are the North Americans. We’re a sizeable minority here. Some make no effort whatsoever to learn German. Why bother? Nowadays, nearly everyone speaks English.

As comfortable as patrician Prenzlauer Berg is for families, there’s no denying that it’s lost its edge. If you want to go out on the town, you usually have to leave its streets for Kreuzberg, Friedrichshain, or Neukölln. Knaack club, which had survived a dictatorship and jarring post-Wall transition, had to close shop because its neighbors in a newly constructed building couldn’t deal with the weekend noise. Every empty lot is being filled, some of them by gated communities, such as the blindingly white Swiss Gardens on the edge of Friedrichshain Park, built on a plot where a caravan community had dropped anchor in the early 1990s. One can only assume that these newcomers behind their locked gates want to keep Berlin out.

So pricey is the neighborhood now that it has come full circle: The artists and the artisans face displacement. Indeed, the owners of my building now have an immensely valuable asset in their hands. Like many of our acquaintances with older leases, we’re fighting tooth and nail to stay.

Undead city

Yet Berlin has clung to its quirky demeanor, and its flair today owes a huge debt to the unpredictable, contrarian currents that course through it. There’s still freiraum, or free space, though it’s harder to come by; today’s brilliant dilettantes have to juggle and skimp to eke out freizeit for their projects. But it’s possible. The Kreativen, or creative class as they’re called today, are integral to the new Berlin. With the choicest downtown addresses out of reach, many of the non-conformists, and along with them the U.S. college grads doing the Berlin thing for a year or two, head toward Wedding and Neukölln, two districts of former West Berlin that back in the day had been populated by proles, migrants, and students. Today those are the neighborhoods we go to for craft beer and live music.

The outré in Berlin hasn’t been eradicated—but rather displaced. The dance clubs, for example, that once lay on the fringes of Potsdamer Platz, the very center of Berlin, journeyed east several miles in the aughts to the banks of the Spree between Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain. While the techno clubs aren’t the otherworldly sensation they were in the 1990s, they remain on the cutting edge of electronic music, aided by the many producers in Berlin, and have expanded their repertoire to include concert gigs, performances, and art exhibitions.

Many artists have migrated beyond the historical city, where they still have a vast pick of freiraum. A 12-minute S-Bahn trip from Alexanderplatz, the old working-class district of Schöneweide has disused industrial warehouses and long-shuttered red-brick factories that now house 400 artists—and with room to spare.

There was a stretch during the 1990s when no one of right mind chose to enter the GDR’s prefabricated cement high-rises, once the modernist pride of the communist state. Yet today, a sunny three-room apartment in Marzahn, Hellersdorf, or Hohenschönhausen goes for about $500 a month—roughly a quarter of the going price in Mitte. There’s not an exodus underway but rather a trickle that could well tick up if inner-city rents continue their rise. In 2012, when the city shut down Kunsthaus Tacheles after investors bought the property, a handful of its exiles, such as the French sculptor Kerta von Kubin and her Italian partner Claudio Greco, transplanted their studio to the high-rise suburb of Marzahn (which is closer to downtown Berlin than Greenpoint, Brooklyn, is to Penn Station), where they joined others escaping gentrification. Now intrepid tourists even make their way out to Marzahn to check out their Kunstwerkstadt and marvel at the living remnants of real existing socialism.

The mainstreaming of Berlin may have elbowed its politics toward the center, but Berlin remains politically charged and home to a sweeping array of activist cabals.

Reclaim Your City (RYC) is a loosely organized outfit that grew out of Berlin’s street art movement—and treads in the footsteps of the great Situationist Henri Lefebvre, author of the classic The Right to the City. RYC understands itself as a network for diverse Berlin campaigns that agitate for affordable living, direct democracy, and the openness of public space to art. The young men and women engage very much in the spirit of Berlin’s squatters and the 1980s Wall artists, but with a contemporary twist. RYC leds protests—including the squatting of public spaces—against the city’s selling off of open-space downtown property in a desperate move to replenish its coffers. Among RYC’s allies are groups such as Kotti&Co, a tenacious tenants’ rights group, in which old and young, German and Turkish, have bonded together to contest the eviction of locals and their shops from the old Kreuzberg neighborhood around Kottbusser Tor, which Berliners refer to as “Kotti.”

One high-profile campaign involving both groups revolved around the Cuvry-Brache, a three-acre plot of wasteland along the Spree in Kreuzberg where assorted nomads had set up a tent-and-hut settlement in the mid-2010s. The lot bordered on two brick tenements whose high windowless firewalls proffered a perfect canvas for two of Berlin’s most iconic murals: the gigantic white creatures of the Italian artist Blu. The first evinced the early struggles of eastern and western Germans in the years after reunification by depicting two floating, vaguely human figures in the act of unmasking each other. The second image, a businessman, his hands cuffed by golden watches, had adorned as many postcards as the floating creatures.

Yet the empty lot and the muraled buildings were central to Mediaspree, a city initiative to turn the banks of the Spree between Jannowitzbrücke and Elsenbrücke into a hub for the media and communications sector. RYC was just one of dozens of civic groups that protested Mediaspree. Nevertheless, the city cleared out the Cuvry lot’s tent city in December 2014, fencing off the property. The next day, in solidarity with the ousted squatters, Blu painted over the giant murals with black chalkboard paint, scandalizing the city and drawing livid op-eds. One of his helpers, street-art aficionado Lutz Henze, explained the surprise move in The Guardian:

Gentrification in Berlin lately doesn’t content itself with destroying creative spaces. Because it needs its artistic brand to remain attractive, it tends to artificially reanimate the creativity it has displaced, thus producing an “undead city.” This zombification is threatening to turn Berlin into a museal city of veneers, the “art scene” preserved as an amusement park for those who can afford the rising rents.

If squatters and artists couldn’t occupy the Cuvry-Brache, then Blu wasn’t going to lend the city or the lot’s owners his artwork—and contribute to the zombification.

Today, Berlin businesses and even local officials hire graffiti artists to decorate their walls for the purpose of stimulating business. Some artists gladly accede, which Blu and his allies argue gives fake, commodified art a prominent place, while open public spaces, where real art can happen, are developed by the very same business interests.

Probably the greatest victory of people power following the torpedoing of the Olympics bid was the preservation of Tempelhof Field. The sprawling 877-acre property—the size of Central Park—in the middle of old West Berlin had been an inner-city airport, the cavernous, polished-marble main hall built by the Nazis. It won international fame as Berlin’s lifeline during the 1948–49 airlift, when over nearly a year some 200,000 flights landed on its runways with supplies for the sealed-off West Berliners.

When in operation, it was always a treat to fly from Tempelhof because it was so easily accessible on the U-Bahn and, because of its diminutive size, quick and easy to navigate. The Nazi architecture, all symmetry and Roman kitsch, lent it a Leni Riefenstahl feel, much like the 1930s-built Olympia Stadium does today. The noise and its size doomed it, though at first Berlin’s politicos had no specific plans for the prime real estate and historic building. But while the city mulled over it, Berliners turned the runway space into Germany’s biggest public park, employing the abandoned tarmac to bike and rollerblade, the grassy field to picnic and fly kites. Neighbors would haul an old sofa and beach umbrella into the park for a day of reading. Baseball diamonds materialized, as well as urban gardening tracts, a self-made mini-golf course, and sculpture gardens.

Unsurprisingly, the choice real estate came into developers’ sights, and the city proposed turning about a third of it into housing and commercial buildings. Since the plans envisioned hundreds of acres for recreational space open to the public, the city was incredulous at the fuss over its blueprint. Nevertheless, so incensed were the plan’s opponents that a civic initiative called 100 Percent Tempelhof Field kickstarted a referendum on the fate of the land, which culminated in over 60 percent of Berliners voting to keep the property intact. The hangars have since been used for concerts, exhibitions, and even the national press ball. For over a year now, the building temporarily houses refugees from Syria and elsewhere. The tens of thousands of migrants—from the Middle East, Africa, and Asia—settling in Berlin will transform the city over the next decades more than anything else. If their presence seasons Berlin’s jambalaya as vigorously as the Turkish migrants did West Berlin in the 1970s and ’80s, the city will be much the richer for it.

Can Detroit Be Berlin?

Long before 2011, when Detroit inquired about simulating Berlin’s resurgence from postindustrial trainwreck to cool-but-safe-for-capital capital city, other cities had picked up on Berlin’s do-it-yourself ethic and upcycling of urban detritus. Yet Detroit looked like a particularly good match: a once proud industrial city reduced to economic disaster zone with sprawling graveyards of vacant factories. In its ruins, artistic energy still flowed, such as in its electronic music scene, a flash of genius back in the 1990s that Berlin borrowed to its own advantage. Thousands of buildings stood empty in the depressed Motor City when Dimitri Hegemann the owner of the legendary Berlin disco Tresor, initiated Detroit-Berlin Connection, a project that aims to inject some of Berlin into its American soul mate. Hegemann zeroed in on two features that Detroit lacked, namely around-the-clock drinking hours and temporary use provisos for derelict properties. The lessons from Berlin: embrace the night and reconfigure space.

But there’s more that other cities can cull from the German capital. Berlin illustrates that cities err to their own misfortune when business interests smother the taproot of urban culture. The creations of artists and outsiders reverberate far beyond their little studios and clubs. Their circles have a value that can’t always, in the short term, be calculated in dollars and cents. City governments may create funds for culture or even farm out studios to artists, as Berlin now does, but more to the point are the conditions necessary to do it yourself. The eccentric and the truly original require space and time. Cities can do most for creatives by preserving low rents with laws that bolster tenants’ rights and cap rent hikes. They must keep neighborhoods livable, and maintain affordable social and health insurance for artists and writers. Berlin’s new as of 2016 left-wing administration in city halls has pledged to do this, but so far we’ve seen very little.

As for creative civil society itself, it has to roll up its sleeves, too. Berlin’s creators have to take up the fight against gentrification, instilling campaigns like RYC and Kotti&Co with the kind of passion that distinguished from-below movements of the past, such as West Berlin’s 1980s squatter movement. The iconoclasts of street art, like Blu, are out in front, battling the commercialization of Berlin—and its art—from the trenches. The movements of bygone eras that mixed subversive politics with subculture and living experiments weren’t one-off flukes of the day. They challenged the status quo—and changed it, inspiring others along the way. With such a wealth of innovative talent in the city, in terms of quantity greater than ever before, today’s international Berliners can make this happen if they take up the fight. If not, they’ll have only themselves to blame when Berlin looks just like Frankfurt, Hamburg, or Munich.

Reference:

[1] In Germany, the creative industries are broadly defined to include broadcasting, music, film, design, publishing, media, advertising, art, the performing arts, architecture, and software development. I do not consider advertising, broadcasting, and software development among the cultural mediums that could constitute critical culture.

[2] ‘DIY urbanism’ in Berlin: Dilemmas and conflicts in the mobilization of ‘temporary uses’ of urban space in local economic development. Workshop ‘Transience and Permanence in Urban Development ’University of Sheffield, 14-15 January 2015

[3] In German they were the Geniale Dilletanten, the word “dilettantes” spelled incorrectly to underscore their amateurism.