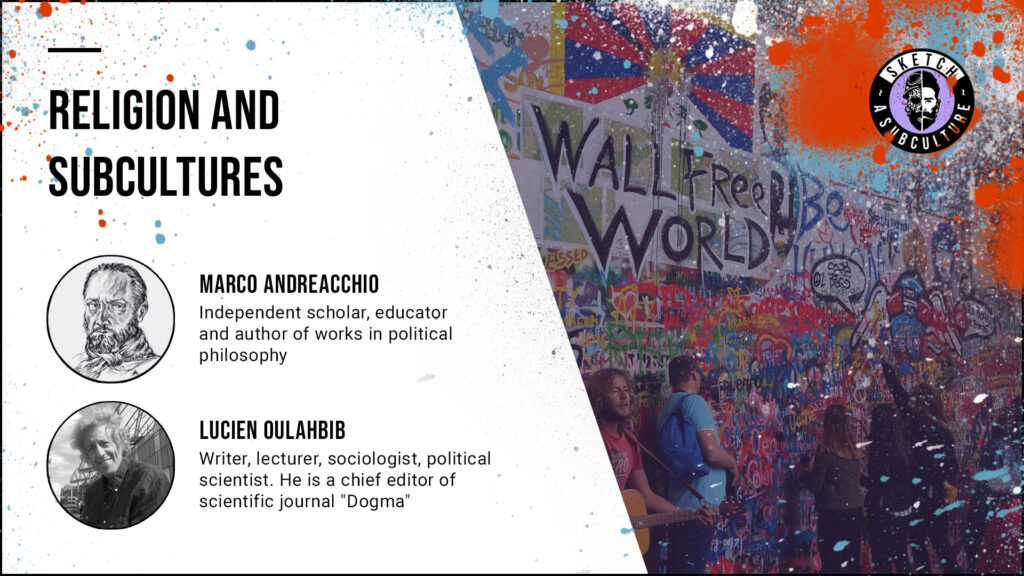

Religion and Subcultures

Marco Andreacchio — Independent scholar, educator and author of works in political philosophy

Lucien Oulahbib — Writer, lecturer, sociologist, political scientist. He is a chief editor of scientific journal «Dogma»

QUESTION 1: The difference between subculture and religion. What are the specific elements that shape each institution?

QUESTION 2: Use of religion by other social institutions (business, politics, etc.) for their own purposes. Religion transformation: from divine transcendence to the universal society based on techno-ideological principles.

INTRODUCTION

At the dawn of modernity, a new way of thinking gave rise to the systematic project of converting Christianity into an apolitical vehicle for the construction of a new «atheological» world. The Christian God was supposed to nourish, so to speak, a humanity gradually weaned from any reference to divine transcendence, in favor of the realization of a universal society and morality based on purely techno-ideological principles. And yet more and more Christians (in Africa, Asia and the Near East, no less than in “the West”) seem to be ill at ease with at least some of our innovations, remaining rather unimpressed by the great strides our societies have made in the direction of anti-humanism. However, there is more to the story.

Today the fundamental terms of all religious discourse are cut off from their original theological-political context, fueling the dichotomy that we, as heirs of modernity, have learned to accept and no longer question, between a supposedly «subjective» or «private» Faith (which is increasingly gasping for air) and a Politics that risks at any moment consolidating into a «socialist» ideology (Dostoyevsky) opposed to all human interiority. Whence, for instance, our habit of speaking of religious faith as if it pertained to whether a divinity exists or not, as opposed to being a matter of trust; so much so that today believing in God seems to be only a question of «wagering» that He exists, rather than trusting in His presence confirmed by a Revelation. Whereas in the first case, we choose to establish a link with the divine, in the second, we respond to the permanence of the divine as a given.

Hence the question that traditional religions implicitly invite us to ask ourselves: is the divine ultimately superfluous to the constitution of a properly human, or political world? The religions suggest a negative answer, of course, but how can any help us, today, understand the relationship between politics and divinity? Is it still desirable for us to seek out mutual compatibility between politics and religion?

Would any traditional religion be able to help us understand even the ultimate and irreducible nature of political action? Could any help us to better understand, not to say overcome the contemporary crisis of our civilization (its loss of confidence) on both the fronts of politics and theology? Would any traditional religion, as it has been represented by the literary heroes of its history, still hold an important lesson for us regarding the problem of mediation between those two ends or modes of happiness (one earthly, the other otherworldly) that the poet Dante, as spiritual father of the Renaissance, proclaimed as proper to man? Or are religions destined to be «secularized» and thus instrumentalized as mere fables?

QUESTION 1:

The modernist attempt to “domesticate” religion by encaging it within the narrow confines of a “subculture” has failed: not only does traditional religion keep trying to ground secular institutions incapable of accounting for their own formal legitimacy; secularism itself begs for a justification it fails to provide before the tribunal of public opinion. The failure of modern secularism amounts at bottom to modernity’s failure to establish a world founded on the allure of power in its multiple guises of finance, arms, “Faustian” technical expertise, seductive grandiloquent propaganda (progressive dream-spinning ideologies), everyday rhetorical flattery and a plethora of strategies of extortion, covert or otherwise, both breading and leveraging popular fear in the attempt to drain our moral resources once and for all. Indeed, the problem of fear stands at the heart of modernity’s present-day crisis.

Machiavellian modernity has yet to tame the fear it has long sought to channel by fueling it, rather than by simply moderating it (as classical philosophy), let alone quenching it (as theocrats of old). Fear has proven resilient, even as it has been systematically packaged for mass consumption, as the consummate merchandise purchasable, not with money, to be sure, but with our own very lives, both physical and moral: we renounce ourselves for it, even as human nature keeps protesting.

Our merchants of fear are at once our providers of antidotes, echoing an old Vincent Price classic of black humor, where murder is lucrative business for the wiliest of undertakers. Prophets of salvation straight out of Dr. Seuss’s Sneetches parable promise us remedies feeding off of collective delusion. And yet, fear remains untamed, forcing tyrants to admit to themselves that they are in the dangerous business of playing with fire. The demand for fear threatens to overload a global industry engaged in both the production and “undoing” of a worldwide web of fear—in both the masking and unmasking of fear as the two poles of a diabolical cycle defining the ongoing steadfast degeneration of civilization into outright barbarism.

Compelled to produce a fear greater than it could ever fathom, the fear industry might very well explode even prior to exhausting our inherited civil resources. That is where old religion resurfaces with untamed force, reminding modern man that his flight from fear was at best a childish way to camouflage the unavoidable, though at worse (and more likely) a masochist exercise into reducing ourselves to a state of the most hapless or radical vulnerability to fear.

Despotic exceptions notwithstanding, old religion distinguishes itself from modernism by presenting fear as, in principle, open to question—or by introducing us to divine mystery as fundamental alternative to the triumph of absurdity lurking behind every corner of the labyrinth of modernism’s progressive endeavors. There where our fear-industry has depleted and reduced Culture to “subcultural” debris, religion exposes itself from beneath the homogenizing veneer of subculture to confirm its true colors, the colors of a fear fostering civilization via moral cultivation, a fear stilling all thought-numbing, free-floating, Chimeric fears; in short, a primordial fear naturally exposed, as a permanently open window, to an Original Blessing. The Religion “resurrected” from beneath the ashes of consumerism, does not sell us new fetishistic fears, but reminds us of the first, the one marking our entrance, nay fall, into this world—a fear prompting us to ask “why?” from the bottom of our souls, instead of leaping endlessly from one fear to another, as if what we really dreaded was the reason why we fear in the first place.

QUESTION 2:

No doubt religion has been made use of throughout the centuries. Yet, the use religions are made of has long been understood as deriving from an original end, a proper telos of religion. To wit, a priest could be a wolf in sheep’s clothing, as long as he appeared as a reminder of the God of sheep. His “job” was to point back to eternal ends, rather than to embody them. So, for a long-time religion was made use of in conformity with religion’s own raison d’être, the reason why the People begged for religion—a reason pertaining to our common need of being reminded, if not of reminding ourselves, that politics is at its best a mirror of theological secrets, as opposed to constituting a flight away from all divine mystery.

Now, today we are systematically taught that institutions have no original meaning, but merely a meaning defined “historically,” by the use people make of them. We are raised to reject the very notion of a religion that transcends the use we make of it by exposing us to the unassailable limits of all “use,” which is to say, to divine ends. Yet the contemporary formal reduction of religion to the plaything of global market forces has not eradicated the transcendent dimension of religion from our societies; it has merely obscured it, making us forgetful of it, even as we remain drawn to it, if only as we are inspired by our collective failure to build a world of means grounding ends, or of means (that which we use) thriving by projecting themselves into unprecedented, innovative, progressive hypotheses.

Once we will have overloaded the market with our fears and desires, religion will once again appear to us as the vessel of a Right (viz., a right way of life) in the light of which the techno-ideological principles of our “universal society” will be forced to melt as waxwings having ventured far too close to the Sun.

We have, in the final analysis, good reasons to doubt the global market’s capacity to manage human nature, especially where, given the secular opposition between Caesar and God, Caesar parades as God, while his adepts posture as Caesars. On such Machiavellian premises, our theater of pretensions appears doomed to succumb to its own logic. For over our Golden Calf swings inexorably a sword of Damocles, to wit, the explosive resentment of an idolatrous people who hate their “God” at least as much as they pretend to love him.

How are we to understand and live the dialectic between Caesar and God without falling prey to the suicidal madness of contemporary secularism? Leo Strauss pointed to the permanent tension between Athens (politics) and Jerusalem (divinity), suggesting the impossibility of a “World Citizenship” that demands the terminal effacing of the visage that Emmanuel Levinas invoked as indispensable element of any life worth living.