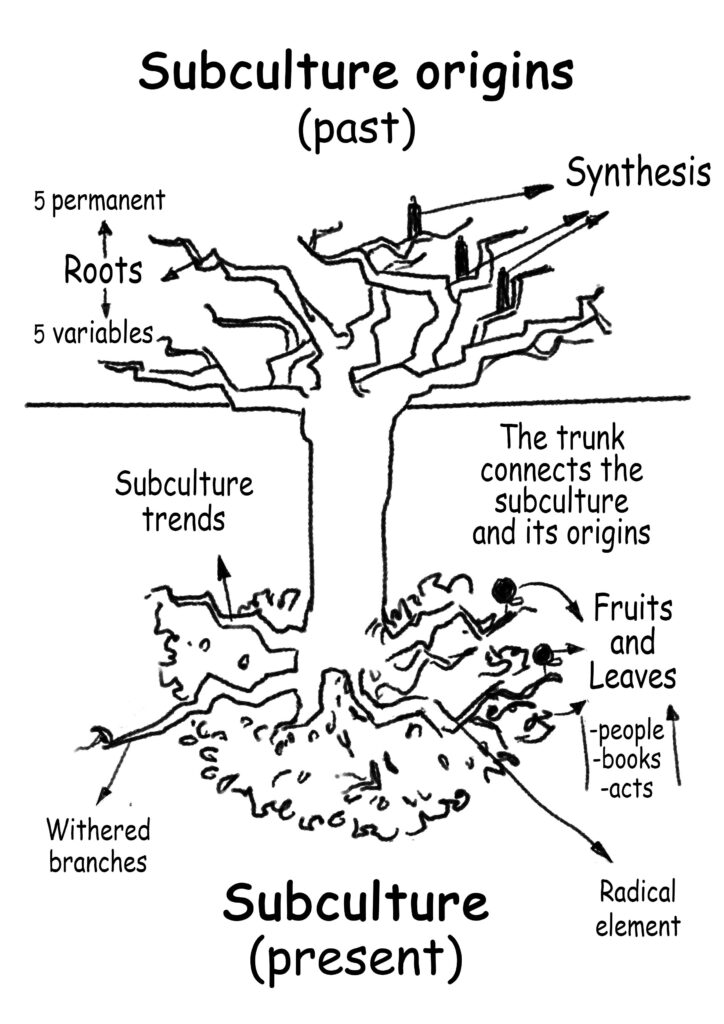

Prof. Frederick Lawrence: The model of an inverted tree for studying subcultures

Matthew Worley — Professor of modern history at the University of Reading and co-founder of the Subcultures Network.

Professor Lawrence’s theory is certainly interesting and it is always useful when people offer means of understanding what are quite loose or amorphous subjects. Subcultures – by their very nature – are nebulous and, quite often, ill-defined. Cultures form organically and change over time, even as they become recognisable and determined by particular modes of practice, language or presentation. In the sphere I am most familiar with — youth subcultures — their understanding and boundaries typically become points of debate or contestation from inside (as well as outside) the cultures. So, while trying to define ‘subculture’ specifically or generally may feel a bit like nailing jelly to a wall, formulas such as that presented by Lawrence are useful in terms of gaining both a sense of how cultures coalesce and develop. And while I don’t recognise Lawrence’s depiction of the ‘modern scholar’ reproducing existing work rather than conducting research, the need for a research plan or process or methodology (my preferred terms to ‘model’) is manifest.

Not surprisingly, Lawrence’s tree motif immediately reminds me of Deleuze and Guattari’s use of the ‘rhizome’ as an ‘image of thought’ suited to understanding the multiplicities of cultural and social development. This, of course, was posited against hierarchal and chronological models – including that of the tree which, as Lawrence notes, has long been presented as a visual aid for understanding social, political, cultural etc structures. But the biological analogy remans. Lawrence adds a mystical twist to this by inverting the tree – revealing the roots and subverting the image to, in turn, reveal the subculture. Quite whether this overcomes the problems of hierarchy and chronology that motivated Deleuze and Guattari is an open question. That subcultures often contain (host may be a better word) their own structures of hierarchy becomes clear once attention turns to how they function and self-realise in cultural form or groups. Likewise, founding myths and competing chronologies suggest that a need for narrative informs cultural perception. And yet, such hierarchies or chronologies remain forever unstable and are oft-contested, raising concern as to whether Lawrence’s model remains too rigid to work with effectively. That it has a distinct beginning and a designated present/end raises questions as to how subcultures come into being and then continue to evolve, mutate and dissipate. Indeed, the boundaries and rigidities that give form to a tree (whatever way round) do not – to my mind at least – lend themselves to the unstructured and often ill-defined existence of subcultures. As for the section on having a maximum/minimum number of roots: I really do not understand this idea and would have to read more of Lawrence’s work to properly grasp it. In the summation we were given, that makes no sense to me. The theory becomes too formulaic – as does the comment towards researching a ‘complete subculture’, which seems to rub against the idea of continual evolution/development. Are subcultures ever complete?

The subverting of the tree does underline another point – or perhaps a presumption. Lawrence suggests that subcultures hold a worldview that is ‘often contradictory to the declared policies of their states’. But is this so? It suggests subcultures are inherently oppositional and feeds into the idea that they must signal a form of resistance. This tallies with a crude reading of the CCCS’ thesis. To be fair, he does say ‘often’ – so I’m being a little crude myself – but it raises a question as to why and how subcultures are ‘often’ read or understood in this way. [The answer may be found in subcultural research stemming from sociological investigations into deviance]

The areas where I am more sympathetic with the model presented here, is in terms of:

- Subcultures continuing to evolve and diverge; of old and new ideas synthesising. The tree motif – like the rhizome in some ways – allows for this to be visualised and understood, albeit within certain bounds

- The analogy of ‘fruits’ appeals as I do tend to see subcultures as creative spaces and often linked to creative processes. It also allows those within the subcultures to be active: they have agency.

- I think, too, in VERY general terms, conceiving of roots, environment, ‘growth’/development and ‘fruits’ can serve as a useful way of approaching how to research subcultures: all are key areas of study.

Overall, then, Lawrence’s inverted tree might serve a useful purpose in helping to visualise subcultural development and the scope of research needed. But the model is by no means absolute and remains too rigid to complement the subject is pertains to help study. I might use his tree to lean on, but not to climb.

As to whether I think one idea informs a whole subculture. Quite the contrary, in that cultures coalesce around and develop from an array of ideas, people, spaces, moods and impulses. I’d go further and say that that is how and why subcultures – or most of them – continue to evolve and mutate over time. Subcultures are contested spaces: their meanings and origins are often sites of debate and tension. In particular, you see tension across generations as subcultures evolve. A constant debate/complaint within subcultures revolves around ‘what went wrong’ or ‘what is diluting’ or ‘distorting’ some kind of pure – authentic – cultural essence.

I’ve been looking at punk and punk-related fanzines recently, from the 1970s–80s.In them you see an interesting pattern. The fanzine writer embraces the culture, writes enthusiastically about and becomes submerged in it. In time, the enthusiasm wanes and reasons are sought for what ‘things are not the same’ – maybe commodification has taken hold? Or people who don’t understand punk are getting involved? Perhaps people getting involved for reasons fashion, so superficially. Or perhaps codification has taken place and people are acting out cliches and stereotypes …and so ruining the scene. Maybe egos have taken hold? I’d suggest variations on this repeat across most if not all subcultures [hence my world being populated by old punk-bores saying it was all better back-in-the-day]. Arguably, of course, subcultures need to evolve to survive in any creative sense — to not become ossified.

Back to the question: Nick Crossely’s work, using Network theory, is interesting in tracing how scenes coalesce. He basically argues that for a scene – and associated subculture -to form you need a certain amount of people to populate it, hence their tending to an urban/city focus. As such, he joins up the connections between people to shows how cultures formulate. I’m doubtful about how definitive this is. Missing for me, is consideration of just what it is that connects the people in the Network. What are the shared interests, ideas, sensibilities? Once you begin to explore theses, then you find commonalities but also variations and points of difference that allow for synergies and divergence. For me, this is why punk – as a cultural term — means different things to different people and evolved across so many sub-strands.

As a caveat, I’d not be so confident in saying this has to be the pattern for all subcultures. I think subcultures vary in their formation and development and that research methodologies need to be flexible in their approach and multifaceted in their application. I’m not convinced there is a definite model or ‘pathway’ through subcultures. As I said earlier, they are necessarily amorphous and any understanding needs to sensitive to an array of contextual factors. And, to finish, I think this a good thing – it helps keep subcultures and our readings of them alive and in motion.